Italy’s Clostebol doping crisis across tennis, football and the Olympics

An anabolic steroid once given to East and West German athletes has resurfaced in elite Italian sport. Honest Sport investigates whether the drug is now being used similarly to testosterone creams.

This investigation into clostebol use in Italy began in 2023, before the world number one tennis player Jannik Sinner twice tested positive for the drug.

You can read a follow-up investigation specifically related to Sinner’s case here (link).

In the months leading up to the 1987 World Athletics Championships, Birgit Dressel had taken a concoction of drugs and medications in order to train harder, and harder, as she sought to bring heptathlon gold home to West Germany. Tragically, Dressel never made it to the Championships nor the Olympics in Seoul the following season. Dressel died from organ failure in April that year.

Dressel passed away in the intensive care unit of Mainz hospital after suffering from paraplegic shock. She had taken copious amounts of narcotics, under the directions of her doctors, to treat painful muscle hardening caused by her anabolic steroid use. Dressel considered anabolic steroids to be harmless which had contributed to her liberal use of the drug class.

“They are all harmless drugs. All athletes take them. It's really nothing special”, said Dressel before her death.

An autopsy revealed traces of 101 different medications in Dressel’s body. At the time, the West German athlete was sadly in the hands of doctors who were so far down the rabbit hole of sports performance that they had lost sight of the line between sports medicine and healthcare. Dressel had been provided steroids by a doctor seen as part-mad, part-genius - Dr. Armin Klümper.

Klümper had also reportedly provided steroids to the Bundesliga football teams Vfb Stuttgart and SC Freiburg in the seventies and eighties. When documents were reviewed in 2015 detailing the substances Klümper had allegedly provided to both clubs, the German national team manager Joachim Löw, who played for both teams at the time, had to answer whether he had visited the doctor’s clinic.

"Of course, I was there a time or two. At 18 or 19, of course, I wouldn't have dared to ask and tell him that I might want to have what he gave me tested in the laboratory. My trust in this profession of medicine was immense," said Löw.

Löw was asked about his relationship with Klümper a year after he led Germany to their fourth World Cup triumph, but the questions concerned events some thirty-five years earlier, although before Klümper had passed away. But it is a substance that Klümper reportedly provided to both Dressel and VfB Stuttgart that has, unlike Klümper, come back from the dead – the anabolic steroid clostebol.

Over the past decade the drug has resurfaced in Italian football and across Italy’s wider sporting landscape. Between 2019 and 2023, 38 Italian athletes have tested positive for clostebol despite the fact it is scarcely produced in oral or injectable form by pharmaceutical companies, as it was during the Dr. Klümper era.

Serie A footballers, tennis players and Olympic athletes in Italy have all had to explain how the steroid accidently found its way into their bodies, and in most cases they have been deemed to have done so convincingly. But an investigation by Honest Sport has now found that cases involving the drug are appearing in small athlete networks. There are also experts in anti-doping who are concerned that clostebol is now being used in cream form by Italian athletes in search of the type of illegal edge once sought by the late Birgit Dressel.

Clostebol arrives in elite Italian sport

“Wake up tomorrow morning…frozen…and to transport you mahogany boxes are needed”.

These were the death threats directed at NADO Italia from Fabio Lucioni’s Instagram account soon after the anti-doping agency sentenced the player to a one-year doping suspension in 2018. Over the course of the previous two seasons, Lucioni had captained his club, Benevento Calcio, to back-to-back promotions from Serie C to Serie A – the most successful period in Benevento’s history.

Unfortunately for Lucioni, his talismanic impact on Benevento would not be felt in Italy’s top-flight division. Lucioni tested positive for clostebol after only the third match of the newly promoted side’s Serie A season. The club captain’s season was over before he knew it.

Even though clostebol is an anabolic steroid that builds muscle mass and enhances performance, an Italian tribunal was lenient with Lucioni and accepted that he had not knowingly cheated. However, the club’s doctor, Walter Giorgione, was banned for four years because he had administered Giorgione a drug from his own personal medical box, rather than the club’s. Giorgione confessed that he had used a spray on Lucioni containing clostebol to help heal the footballer’s cut more quickly.

The Lucioni case made national news, but it did not serve as a cautionary tale to Italy’s elite athletes. The number of clostebol cases in Italian sport ranges far and wide across the country. Italian athletes have tested positive for the drug before the Olympics, four tennis players have been caught for clostebol and two basketballer players on the same team were careless enough to both ingest the anabolic steroid.

Four years after the Lucioni case, two Italian junior tennis players, one just seventeen years old at the time, tested positive for clostebol within three months of each other. One of the players Matilde Paoletti, who played at the Junior French Open, was training at the Olympic training centre in Formia in 2021, the year she was caught. The other Mariano Tammaro, a minor, was a top ranked world junior, and in 2021 was training under the national team coach.

Any concerns that these players were the victim of child doping were officially misplaced. Paoletti tested positive after petting her pet chihuahua who had been administered clostebol spray by her mother to heal a wound. While in the case of Mariano Tammaro, his father applied a spray to a wound on his son’s knee.

But away from tennis, the spray of clostebol cases has been felt further across Italian sport.

When the girlfriend of the Olimpia Milano basketballer, Riccardo Moraschini, sliced her finger while cooking, she used a clostebol spray to heal the cut. Like Lucioni’s doctor, Paoletti’s mother and Tammaro’s father, she was unaware that clostebol was prohibited for use in professional sport. Unfortunately, when she naturally came into contact with her boyfriend, clostebol unknowingly entered his system. Equally unfortunately for Olimpia Milano, Italy’s most successful basketball club, their power forward Christian Burns had tested positive for clostebol two years earlier.

And, in pre-games doping testing before the 2016 Rio Olympics, two qualified athletes both tested positive for clostebol, out-of-competition in the month of July. Both athletes, the volleyball player Orsi Toth and the sailor Roberto Caputo, missed the Rio Olympics for Italy.

Italy has quite clearly been in the midst of a clostebol crisis, of some form or another, for much of the past decade. A decade in which clostebol detection methods have become more sensitive.

According to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), half of the world’s clostebol cases come from Italy. A statistic partially explained by the fact that Italy is one of the only remaining countries in which clostebol is still sold.

When WADA banned the heart medication Meldonium in 2016, the drug at the centre of the Maria Sharapova affair, the hundreds of positive cases were largely concentrated in Russia. In order for an athlete to test positive for a drug, inadvertently or not, the drug has to be available in their geographical location. Therefore, doping cases involving specific drugs can be location specific.

Outside of Eastern Europe, Meldonium is not widely available. Therefore most of the cases involve Russians. Outside of Italy, clostebol is not widely available in Europe, therefore the majority of cases involve Italians.

It remains bewildering, however, that Italy’s athletes are missing the warning sign printed on clostebol creams and sprays in Italy, which clearly states that the product contains ‘doping’ substances.

Clostebol readily available in Italian pharmacies

During the time Dr. Armin Klümper was reportedly supplying clostebol to Bundesliga football clubs the drug was sold under the brand name Megagrisevit-Mono®. Megagrisevit was an injectable and at the time was marketed by the Italian pharmaceutical company Farmitalia.

The drug was initially developed in East Germany, before it was synthesised with other drugs and given to the state’s Olympic athletes, but since the collapse of the Berlin Wall the drug is scarcely available in Europe.

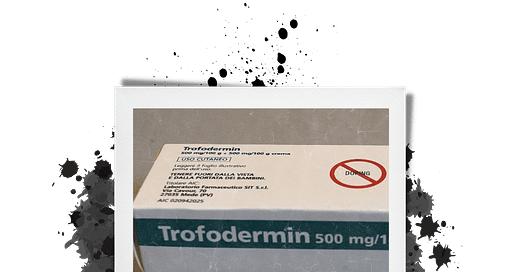

However, in Italy and Brazil, the countries faced with the most clostebol cases, the drug can be bought in pharmacies without a prescription. In Italy, it is most commonly sold in cream form as Trofodermin, and a tube can cost as little as twelve euros. Trofodermin is applied to the skin to treat abrasions, lesions, burns and infected wounds.

If an athlete handles the cream, even in applying it to another individual, then they can risk testing positive. This has been one of the common defences used in Clostebol cases. And in 2020, this defence was assessed in a controlled experiment by scientists at Rome’s anti-doping laboratory and published in the paper, ‘Detection of clostebol in sports: Accidental doping?’. Scientists were able to detect Clostebol in the urine of a subject who had applied Trofodermin cream to another individual.

But it is a sentence within that paper that perforates the argument that only the innocent have befallen to the clostebol curse. “According to Italian law, a visible sign indicating the presence of a substance included in the WADA list of prohibited substances must be present”, reads the paper.

Trofodermin cream, as mandated by law, is sold in a packaging emblazoned with a warning that the product contains a doping agent. This warning would seemingly make any argument of inadvertent use untenable. A warning so problematic that athletes’ lawyers have had to address the warning head-on during disciplinary hearings.

For example, in perhaps the most famous clostebol case, the Norwegian Olympic skier Theresa Yohaug claimed to have tested positive for the steroid after applying Trofodermin cream to treat her sunburn while training in Italy. Yohaug acknowledged she had seen the packaging, but an independent tribunal still accepted she had missed the red warning sign on the box. She was allowed to return for the Beijing Olympics in 2022 and win three gold medals. At those same Olympics the Spanish skater Laura Barquero tested positive for clostebol. To no surprise Barquero is based in Italy.

Anti-doping insiders are now concerned there is another reality to at least some other clostebol cases. Trofodermin is a cheaper, more obtainable alternative to testosterone gels for athletes operating on the darker side of sport.

Clostebol creams, testosterone gels and passing drug tests

“It will be interesting to determine the minimal amount of topical male hormone required to create a positive test".

In the summer of 2009, the Nike Oregon Project coach Alberto Salazar exchanged emails with the Nike CEO Mark Parker about arranging an experiment to determine how much testosterone gel could be applied to skin before an athlete failed a drugs test.

Salazar, who was banned for trafficking testosterone as part of the experiment by US Anti-Doping Agency, claims that the genesis of the experiment arose after he became concerned that rival athletes may sabotage his runners by rubbing drugs onto them after races. To dampen his concerns, Salazar wanted to ensure that, even if his athletes were sabotaged, they would not fail a drug test.

The other explanation was that Salazar wanted to ascertain how much testosterone a doping athlete could take without testing positive. A narrative, while still contested, made more believable when a Nike Oregon Project whistle-blower released a document that stated Salazar’s runner Galen Rupp had been on testosterone since he 16 years old. Both Rupp and Salazar said the document was inaccurate. The same whistleblower, Steve Magness, saw testosterone on the kitchen counter of an apartment shared by Salazar and Sir Mo Farah at a training camp in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 2012.

Whilst the purpose of Salazar’s experiment is still disputed, testosterone gels have long been used in professional sport. The BALCO chemist Victor Conte, after being arrested by the FBI, admitted that he had provided the former sprint queen Marion Jones with testosterone creams before the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

Conte also provided the creams to baseball players and explained that testosterone cleared the system so quickly that baseball players were taking it daily, and still not testing positive. When testosterone gels are applied to the skin regularly, the accumulation of testosterone helps athletes build muscle and boost their haemoglobin, the oxygen carrying capacity of their blood.

Despite the cumulative effect of testosterone, the athlete never tests positive as they only take a small amount each day.

“Currently a player can go home or to the hotel after a game, use a testosterone cream, gel or patch, and it will be undetectable by the time he goes to the ballpark the next day. I think these guys are using testosterone every single day of the week," said Conte in 2013.

Salazar, and his disgraced doctor, Jeffrey Brown were able to ascertain that an individual could apply four pumps of testosterone gel yet pass a drug test an hour later. The experiment took place on Salazar’s sons at the Nike Labs in Oregon, USA.

The former head of the Portuguese anti-doping agency, Luis Horta, has now told Honest Sport that he is concerned that sports doctors have begun to use Clostebol creams as they do testosterone gels.

“I think there are some doctors involved in doping strategies that are using this strategy to avoid detection or to have a low risk to be detected”.

In 2019, Salazar’s trusted doctor Jeffrey Brown was suspended by USADA for possessing and trafficking testosterone.

“I suspect that they use creams. Because creams as clostebol, or testosterone by cream or by gel. The detection window it's very, very short. It's sometimes some hours, then it's a good way to dope. With a lower risk to be tested, positive,” Horta told Honest Sport.

Clostebol creams are less potent than testosterone gels, so the performance-enhancing effect is more debatable. However, athletes often inject a stronger anabolic steroid, and then ‘top themselves up’ with weaker creams as competition, and more drug testing, approaches.

“It's like with a bathtub. The shot fills the tub. The cream keeps replenishing it every day to top it off,” a sports medicine doctor once said about testosterone creams.

Horta, who has also worked in Brazilian anti-doping, says he has been involved in at least one doping case in which he had suspected the athlete had been using clostebol as a doping agent.

“In one case the athlete received the standard punishment because he couldn’t explain the case. In another case the athlete had a reduced sanction because he demonstrated that was negligent by applying a cream with clostebol on his dog without using gloves,” said Horta.

There are numerous cases to support Horta’s affirmations. In 2023, the Italian tennis player Stefano Battaglino was banned for four years after he failed to show that he had taken Clostebol inadvertently. And curiously before the 2010 Commonwealth Games, the British shot-putter Mark Edwards tested positive for both clostebol and testosterone. He was not able to prove a lack of intent.

When Honest Sport asked a leading scientist at a WADA-accredited laboratory whether they too suspected that clostebol creams were being abused, they wondered whether it was instead still being used in injection, rather than cream, form.

“My perception is that the use of clostebol cream (e.g. trofodermin), in common therapeutic amounts, is hardly performance-enhancing, but despite the limited availability of other formulations (of clostebol), the misuse by other routes (e.g. injection) cannot be excluded, and differentiating by analytical means between the ways the anabolic agent entered an athlete’s organism is difficult. Hence, disregarding clostebol (as a doping agent) is probably not an option.”

A Carabinieri police officer in Italy told Honest Sport that it is rumoured that clostebol creams may be being used to hide the presence of other more potent doping substances.

“I heard other rumours, i.e. that it can be used to mask another substance. That means to hide positives for other substances that must have been taken advertently, and it interferes with laboratory analysis. Even in this case only science can tell us if it is legends, or if it is reality,” said the source.

Whether by injection, or by gel, or whether used as a masking agent, there is obvious concern surrounding the number of ever-continuing clostebol cases in Italy, and it is the ever-presence of doping doctors in professional sport that raises that concern higher.

Doctors never far away in doping cases

Olimpia Milano are the most successful basketball team in Italy, and have won 30 Italian basketball league championships, but in the spring of 2022 the club was facing a moment of shame rather than glory.

The club was in the midst of its third anabolic steroid case in just three years, and it was the presence of a doping doctor in the background that increased the severity of the case.

After a match against Real Madrid in March 2022, the Greek forward Dinos Mitolgou tested positive for the anabolic steroid Dianabol. The case had arisen shortly after two of the club’s players, Riccardo Moraschini and Christian Burns, tested positive for the much-discussed steroid Clostebol. The cases came in 2019 and 2021, respectively.

Dianabol, like clostebol, was originally developed in the 1950s and marketed in Germany. It is an immensely potent anabolic steroid that was administered to the entire USA wrestling team at 1960 Olympics. It has obvious performance-enhancing benefits.

During the time Mitoglou was waiting for a decision in his case from the Italian anti-doping agency, the Greek police raided the premises of his sports medicine doctor on the outskirts of Athens.

Since March 2020, the doctor had been supplying athletes with prohibited doping substances. The doctor procured the substances from Bulgaria, imported them to Greece and re-labelled them in order to convince her clients that they were approved medicines.

Mitoglou was able to argue that he had been doped with a serum unknowingly. The doctor claimed otherwise.

“The doctor assured me that the tablets were a 'miracle drug' from Russia’. She gave me a clear serum. After my related question, she answered me that this serum would help to...cleanse my body", said Mitoglou.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport believed Mitoglou and significantly reduced the 36-month sanction he had been dealt by NADO Italia. Olimpia Milano maintained their zero tolerance to doping, and quid pro quo their lack of involvement in Mitoglou’s case.

Nevertheless, the case serves as a reminder that doping doctors are never too far away in many doping cases, and Honest Sport has now found that a sports doctor, who is not Italian, was reported to anti-doping authorities in 2016, who later had one of his athletes test positive for clostebol.

A whistle-blower sent the agency in question a photograph of a bottle of pills that a sports doctor had prescribed. The prescription was for the anabolic steroid oxandrolone. The patient’s name had been redacted in the photo and therefore it was not known if the steroid was prescribed to an athlete. The doctor could therefore not be sanctioned. Officially, that was the outcome of the incident.

When an athlete the doctor was treating tested positive for clostebol they, too, were cleared of knowingly doping, as is so often the case.

But as the Italian Carabinieri officer told Honest Sport, the sheer number of clostebol cases, at least in Italy, can no longer be considered an anomaly.

“Of course, except in cases of accidental doping, if the use of a substance spreads it’s not just a coincidence.”

It is now the decision of anti-doping authorities to determine how seriously they want to investigate Italy’s problem with a drug once central to the East German, and West German, doping programmes.

This investigation into clostebol use in Italy began in 2023, before the world number one tennis player Jannik Sinner twice tested positive for the drug.

You can read a follow-up investigation specifically related to Sinner’s case here (link).

If you would indeed like to share this article on social media please share the following proxy link as Twitter and Facebook silence normal Substack URLs because it is a competing platform:

https://substack-proxy.glitch.me/articles/honestsport-substack-com-p-italys-clostebol-doping-crisis-across.html

Every Monday and Thursday, I publish a weekly press-round up of all the doping stories in the media from the past seven days.

In the Town Square, you can find recommended articles, documentaries, books, reports and websites to learn about doping in sports, how it works, and understand what it is like to dope. It is also a place where I post about recent anti-doping issues.

Wow, this puts things into perspective with the whole Sinner scenario. How can anybody say they have not been rubbed on by their PT! More testing needs to be done to show where the line is. Regardless Sinner was shown preferential treatment versus others accused for similar. They waited much longer.

Thanks for this, insightful, interesting in light of the previously squeaky clean Sinner revelations today.