Up to 103 tennis players failed doping tests and escaped bans

In 2018, 72% of players who were caught with drugs in their system were not punished. The same year, the International Tennis Federation reduced blood doping tests by 40%.

It takes considerable time and effort to run this newsletter, and paid subscriptions help greatly. If you would like a group subscription for your organisation please reach out directly at honestsport@substack.com.

Thank you to those of you who have decided to subscribe already.

Help grow this newsletter by sharing it with friends, athletes or colleagues, particularly anti-doping officials, journalists or sports lawyers, who you think would find it useful or interesting. Thank you, Edmund!

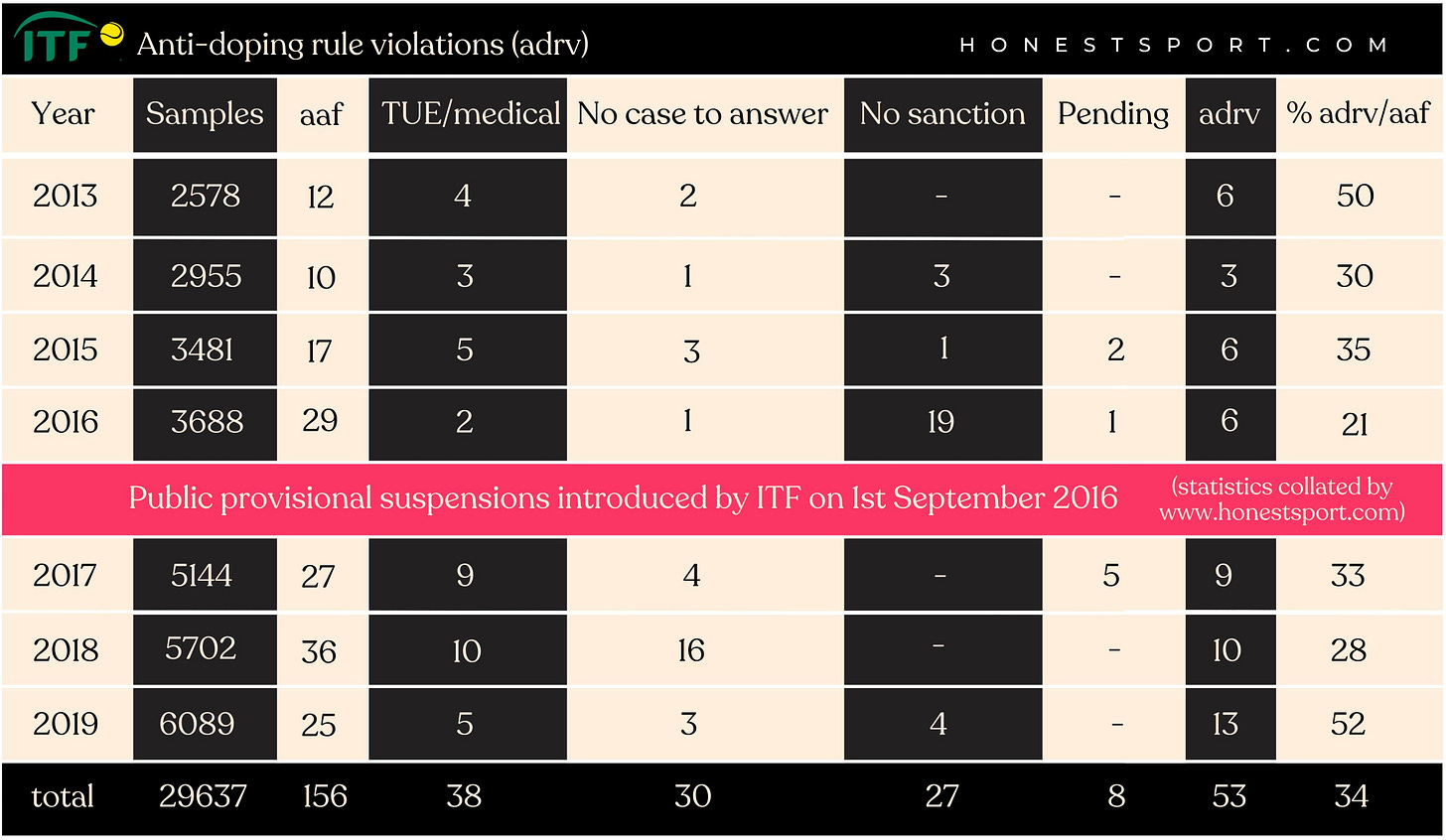

As many as 156 professional tennis players failed drugs tests between 2013 and 2019, Honest Sport has found, and only one third of them (34%) were sanctioned.

In 2016 alone, 19 players who were charged with a doping offence escaped a ban yet only two of those cases were made public.

In 2018, 16 players were deemed to have “no case to answer” by the International Tennis Federation (ITF), and 72% of all players who tested positive that year were not suspended from professional tennis.

The identity of the majority of these players, the substance they tested positive for and the reasons as to why they were cleared of all charges has never been made public.

The ITF, since September 2016, has publicly announced all provisional suspensions. However if a player tests positive for “Specified Substances”, such as asthma drugs, diuretics or corticosteroids, they can refuse a provisional suspension and continue competing. This also applies in swimming, cycling and track and field.

Between 2013 and 2019, the International Cycling Union (UCI) sanctioned 46% of athletes who failed a doping test while World Athletics banned 49%. The International Swimming Federation (FINA) has the lowest conviction rate at 28%.

Before this year’s Wimbledon, a Mail on Sunday investigation found that the International Tennis Federation (ITF), before some major tournaments, including grand slams, warns all competing players that they will be subject to Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) testing, a tool used to detect blood doping indirectly.

The ITF’s own rules state that players should be given “no advance notice” of any doping tests save for in “exceptional and justifiable circumstances”.

Now Honest Sport has found that, starting in 2018, the ITF reduced the number of direct blood doping tests conducted by 40%.

Every season, the ITF subjects the world’s top 100 male and female singles players, who comprise the ITF’s registered drug testing pool, to both in- and out-of-competition doping tests. Players must provide information of their whereabouts for an hour each day of the year so that they can be located for doping controls.

According to World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) statistics, the ITF collected 29,637 blood and urine samples, between 2013 and 2019, from players both inside and outside the world’s top 100.

Only 156 of these 29,637 samples were found to contain a prohibited substance – a rate of 0.5%.

Every time a professional athlete fails a doping test, the relevant anti-doping body will make sure the drug test was carried out conforming to international standards. If this is so, and the athlete does not possess a medical exemption to take the drug, and the anti-doping body believes the athlete has a case to answer, then they are charged with an anti-doping rule violation and, in many cases, provisionally suspended.

The athlete then has the opportunity to defend themselves against the anti-doping agency’s charge at an independent tribunal.

Honest Sport has found that of those 156 positive doping samples, which were ruled adverse analytical findings (AAF), only 53 of them (34%) led to a player being convicted of an anti-doping rule violation (ADRV).

Neither the 2020 nor 2021 statistics have yet been published by WADA.

This means that as many as 103 tennis players failed a doping test between 2013 and 2019 yet faced no sanction.

It is not discernible from public statistics whether any players tested positive more than once time over this time period.

In professional swimming, 25 of 90 (28%) athletes who tested positive were sanctioned by FINA while 226 of 489 professional cyclists (46%) were sanctioned by the UCI. World Athletics sanctioned 146 of 300 athletes who failed a doping test (49%). Several cases were pending at the time the statistics were released.

Some years the large majority of athletes in these sports escaped sanction. In swimming, in 2016, there were 22 AAFs but not a single swimmer was sanctioned by FINA. In 2018, 72% of tennis players who failed a doping test avoided a ban.

However, there are, of course, legitimate reasons as to why a positive drugs test may not lead to an athlete serving a doping ban.

For example, there could have been a break in the chain of custody of the sample or the source of the positive test could have been from a legitimate medical treatment or contaminated nutritional supplements.

In fact, one quarter of tennis players (38/156) who failed a doping test had, either a medical exemption (TUE) to take the drug or had another medical issue that had led to their failed test.

The ITF’s TUE system, however, has faced scrutiny in the past.

In 2013, the 2016 Olympic mixed doubles gold medallist Bethanie Mattek-Sands, who won the US Open with Jamie Murray, was granted a medical exemption to take the steroid DHEA to treat her alleged adrenal insufficiency. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) appealed the ITF’s decision and Mattek Sand’s TUE was revoked. It later emerged that the doctor who had prescribed her drugs claimed to have worked with “thousands of steroid-using athletes”.

But not all players who tested positive and escaped sanctioned were in possession of a TUE. There were as many as 57 players who were not in possession of a medical exemption when they tested positive between 2013 and 2019.

Yet, 30 of those maximum 57 players were still found to have “no case to answer” by the ITF. They were neither charged with a doping offence nor did they have to defend themselves at a disciplinary tribunal. As a result their cases were not made public.

Another 27 of those maximum 57 players were charged with an anti-doping rule violation but received “no sanction”. In 2016 alone, 19 players were dealt “no sanction” and escaped all punishment. Only two of these cases, both for meldonium, were made public according to the ITF.

The reasons for which many tennis players were cleared of doping offences over this period is unknown to the public because the ITF only started announcing all provisional suspensions in September 2016.

The ITF made this amendment to their rules in an attempt to dampen persistent rumours that players had been serving “silent” drug bans.

The ITF said in a press release, “From 1 September 2016, if a case arising from the Tennis Anti-Doping Programme results in a provisional suspension, then that provisional suspension will be made public.

The reputation of the Tennis Anti-Doping Programme and, consequently, of tennis, have been damaged by accusations that players have been allowed to serve bans without those bans being made public (so-called ‘silent bans’).”

In the following two seasons, in 2017 and 2018, zero players, who were provisionally suspended, escaped a doping ban. However, in 2018, 16 players tested positive for drugs but, despite not possessing a medical exemption, were deemed to have “no case to answer” by the ITF.

Consequently, since they were not provisionally suspended, as they were found to have “no case to answer”, their identities were never revealed to the public.

The ITF still does not automatically suspend all players who test positive for banned substances. In certain cases involving “Specified Substances”, such as asthma drugs, diuretics or corticosteroids, players can refuse a provisional suspension and continue competing. If they are eventually cleared of a doping violation then the ITF does not have the right, without the player’s permission, to publicise the case.

These procedures are outlined in the WADA code and as such other International Federations such as the UCI, FINA and World Athletics follow these same guidelines.

WADA says that positive drug tests for Specified Substances do not lead to mandatory provisional suspensions because “Specified Substances are more likely to have been ingested for reasons other than for sport performance, as stated in Comment 26 of the World Anti-Doping Code”. Anti-doping rule violations involving Specified Substances are subject to a more flexible sanction.

In June, a Mail on Sunday investigation, found that the ITF had warned all competing players before some major tournaments, such as the 2021 US Open, that they would be subject to Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) testing.

The ITF’s own anti-doping rules state that all doping tests should be conducted “without advance notice to the player” save in “exceptional and justifiable circumstances”.

The ABP expert, Rob Parisotto, an Australian stem-cell scientist who pioneered the first test for Erythropoietin (EPO) and was a member of the UCI’s expert ABP panel, stated that the ITF was potentially allowing tennis cheats to escape detection.

“It does make a huge difference if testing is known in advance with regards to blood doping. A three- to four-day window before a tournament would be the ideal period to ‘top up’ your blood volume to maximise oxygen-carrying capacity and therefore improve endurance and recovery capabilities,” said Parisotto.

During the US Anti-Doping Agency’s investigation into systematic doping by Armstrong, the cyclist’s US Postal team-mates admitted that they regularly manipulated their blood parameters, with the help of a Spanish doctor who also worked in tennis, using saline infusions when they knew they would be drug tested.

Honest Sport has now found that at the beginning of the 2018 tennis season, the ITF reduced the amount of direct testing for blood doping by 40%. In 2018, the ITF analysed 605 doping samples for EPO, which was down from 1009 in 2017.

In 2019, 618 samples were tested for EPO before the Covid-19 pandemic understandably hit numbers in 2020.

When Honest Sport asked the ITF why they had reduced EPO testing so significantly it said “the reasons underlying changes to the test distribution programs are confidential”.

None of the 156 positive drug tests between 2013 and 2019 were for EPO.

In 2013, as part of an anonymous survey performed by academics at the Universities of Ljubljana and Split, 76% of male and 47% of female players, who were competing at ITF events, disclosed that they believe tennis had some form of doping problem.

16% of the players in the sample pool noted that doping occurred “often” in tennis.