The Clenbuterol Cloud hanging over British triathlon

A British triathlete has been found in possession of clenbuterol tablets, after another British triathlete was cleared after testing positive for clenbuterol at the 2016 World Triathlon championships.

It takes considerable time and effort to run this newsletter, and paid subscriptions help greatly. If you would like a group subscription for your organisation please reach out directly at honestsport@substack.com.

Thank you to those of you who have decided to subscribe already.

Help grow this newsletter by sharing it with friends, athletes or colleagues, particularly anti-doping officials, journalists or sports lawyers, who you think would find it useful or interesting. Thank you, Edmund!

The Outer Temple chambers, just a stone’s throw away from London’s Fleet Street, is home to almost one hundred barristers and solicitors who represent clients in legal cases ranging anywhere from white collar crime to land disputes.

But it was a short press release, posted on the chambers’ website, one December morning, that almost brought the world of British triathlon to its knees. The post wrongly implied that there was a one in four chance that one of Alistair or Jonny Brownlee, the British triathlon brothers who starred at London 2012, had failed a doping test in late 2016.

The press release stated that an elite male triathlete had tested positive for clenbuterol, which has anabolic properties, at the World Triathlon Championship in Mexico. The intention of the post was perhaps to tout the expertise of the lawyer who represented the athlete, but in doing so the text revealed potentially key information concerning the identity of the British triathlete in question.

The year was 2016. The ‘World Championships in Mexico’ referred to either the World Triathlon Grand Final or Aquathlon Championships in Cozumel, Mexico. The word ‘he’ narrowed the group of fingered athletes to males competing at the events. But then, the use of the term ‘elite’ suggested that the triathlete was one of the following – Adam Bowden, Tom Bishop, Alistair Brownlee, Jonny Brownlee or Richard Allen.

In triathlon, the word ‘elite’ specifically refers to professional World Triathlon categories, and at the two World Triathlon events in Cozumel there were only two elite male races (Elite men’s triathlon, elite men’s aquathlon). The five aforementioned athletes were the only Britons competing. If the word had been used as intended, the athlete had to be one of the five.

As news of the scandal broke, the word ‘elite’ was removed from the original post, thus widening the pool of athletes significantly. The post was then taken down all together. A seemingly innocuous press release had created a storm in British triathlon.

British Triathlon was forced to make an official statement. The federation did not specifically deny that the athlete came from the original group of five, but it stated that the triathlete was not part of ‘British Triathlon’s World Class Performance Programme’. It was understood that Bowden, Bishop, the Brownlee brothers and Allen were all a part of this programme, and it therefore had to be assumed that none of the five had tested positive for clenbuterol.

Further, the athlete was cleared by World Triathlon. The federation, along with the with World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), had decided that the source of the drug in the triathlete’s doping sample was likely to be from contaminated meat consumed in Mexico, where clenbuterol is used to fatten livestock.

Case closed, yes – but the intrigue now continues.

Clenbuterol has long been used by triathletes to illegally enhance performance. In 2013, the Spanish military police, the Guardia Civil, dismantled a doping network in which a pharmacy in Andorra, where many triathletes train, mailed prohibited substances to many athletes, as well as eleven sports doctors, throughout Spain.

The Guardia Civil, in what is known as Operacion Cursa, intercepted phone calls between the Spanish triathlete Xavier Llobet, who competed at the 2004 Athens Olympics, and a cyclist during which they discussed the price of clenbuterol, referred to as ‘clembu’. It was clear the drug was being used by the triathlete to engage in doping.

Dealer: Do you want two clembus (clenbuterol) or one?

Llobet: One, one, one, one, one, yes, put one, but then it's less. Then there are six... Well 700, 700.

Dealer: Each box of clembu (clenbuterol) costs 60, but they cost more.

Llobet: Well, 700, in the end it's 700 euros. Fair.

Dealer: Okay, wait, three Acts, a clemb...

The benefits of clenbuterol to triathletes are clear. ‘Clen’, as it is commonly known, is a fat-burning drug that also builds muscle. The drug increases body temperature through a process called thermogenesis. Once the body’s temperature is increased, one’s metabolism is then primed to burn off more calories. However, because clenbuterol raises systemic body temperature, it can cause tremors and severe anxiety.

Nonetheless, triathletes take clenbuterol to burn body fat and lower their overall weight. The less weight they have to transport around a triathlon course, the faster they are.

The drug has now found its way into British triathlon circles.

In February 2023, a British Age-Group (amateur) triathlete was in the car of her then-boyfriend Louis Walker, also a triathlete, when she discovered a box of clenbuterol tablets, branded Clenoxin, belonging to Walker. Both Walker and his ex-partner competed in the amateur category at the 2023 World Triathlon Championships in Ibiza, Spain.

Upon discovery, Walker’s then-girlfriend immediately confronted him and he promptly admitted that he had been taking clenbuterol for the last two weeks. She informed Walker’s triathlon coach and he was quickly reported to UK Anti-Doping (UKAD), the agency that patrols doping in Britain.

It soon became unequivocally clear that Walker was knowingly doping in an attempt to enhance performance. On 3rd April, Walker told UKAD that he had been taking one Clenoxin pill a day in a bid to lose weight in the ten days before his drugs were discovered. He admitted to storing them in his car.

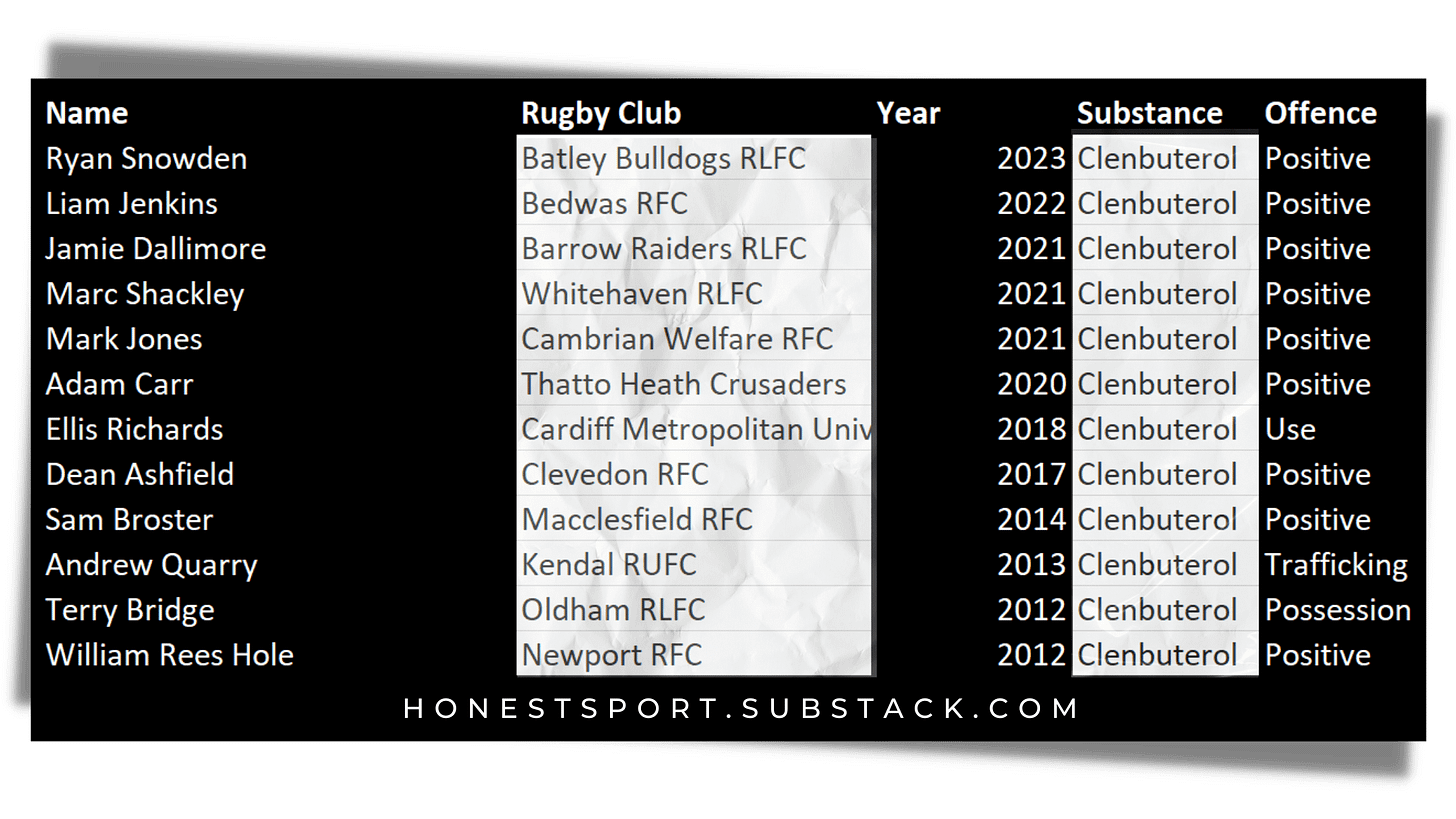

Walker’s case, as well as 12 British rugby cases in which players have either tested positive for or been found in possession of clenbuterol, demonstrate that the drug is not hard to come by in Britain. The different types of doping substances taken by athletes from different countries can vary depending on the availability of a drug in a certain country. In Britain, Clenoxin tablets can be readily purchased online for £46. Walker said he purchased the drugs in a local gym.

Despite Walker’s confession, he was allowed to compete at the World Championships 26 days later. He finished 32nd in the 25-29 age group amateur duathlon sprint event. Finally, nine months later he was banned by UKAD for three years for the possession of a prohibited substance.

In some instances, an amateur doping case such as this would have little significance to the world of elite sport, but the Walker case casts new doubt on whether we can blindly trust the decision made by World Triathlon to attribute the 2016 British athlete’s clenbuterol positive to meat contamination. A decision shrouded in a cloud of opacity, set against a background of both clenbuterol use across the sport and meat contamination in Mexico.

In 2010, a Brazilian triathlete, Raphael Menezes, failed a test for clenbuterol, also in Mexico. He was charged with a doping offence and was required to defend himself in front on an independent tribunal. His defence, which relied on meat contamination in Mexico, was rigorously examined before it was finally rejected and he was suspended for two years.

In 2008, an International Olympic Committee witness testified that clenbuterol cases were “very rare and unlikely to occur and, even then, solely under very specific and extreme circumstances”. This evidence was presented in the case of the Polish canoeist Adam Seroczynski who tested positive for the drug at the Beijing 2008 Olympics. He too was banned for two years.

The British athlete was not subjected to the same procedure.

According to the British Triathlon press release, the British athlete was deemed to have ‘no case to answer’ meaning that he was either never charged with a doping violation or the charge was later withdrawn.

According to the WADA ‘Anti-Doping Rule Violation Report’, it lists three examples in which an athlete may have ‘no case to answer’. “Such cases include for example: authorized route of administration for glucocorticosteroids; departure from International Standards; or cases outside of WADA’s jurisdiction”. None of these examples applied to the British athlete.

World Triathlon, whose vice-president was the head of British Triathlon at London 2012, and WADA still decided to close the case even though clenbuterol contamination cases apparently only occur under ‘very specific’ conditions. The facts of ‘his’ case nor the detail of ‘his’ defence have ever been shared publicly. They therefore cannot be examined alongside the other legitimate clenbuterol contamination cases that have occurred in Mexico.

At the 2011 Under 17 FIFA World Cup in Mexico, over one hundred players tested positive after unknowingly eating contaminated meat. Earlier this year, the British tennis player Tara Moore was cleared after testing positive for the anabolic steroids nandrolone and boldenone, which are both used to fatten livestock in Colombia.

Moore presented detailed evidence concerning which restaurants she had eaten at in Colombia, how much meat she had consumed and whether these amounts were consistent with the drugs found in her doping sample. A panel ruled that another tennis player, who tested positive at the same tournament in Colombia, was also a victim of contamination. The decision can be read in full on the tennis anti-doping agency’s website. The agency has appealed the decision.

The British triathlete’s case was dealt with differently, and behind closed doors. The athlete may well have been a victim of meat contamination but the legitimacy of ‘his’ defence was not examined at a rigorous independent tribunal, as part of disciplinary proceedings. At most ‘he’ was subjected to a preliminary hearing.

There were also no reports of any other clenbuterol positives at the same event. All we know is that British Triathlon’s failure to warn the athlete that meat contamination was common in Mexico was factored into the decision to close ‘his’ case.

Ultimately, one is left wondering how differently the case may have unfolded had it played out in the public arena.

Transparency breeds integrity, and, without it, a cloud will always hang over those cases in which it has not been exhibited.

You can add this British triathlon case to the list. As for ‘his’ identity it will seemingly never be known.