Why Jannik Sinner could still be banned - Town Square #10

The World Anti-Doping Agency's appeal in the player's case will be heard by the Court of Arbitration for Sport in April. Sinner's future hinges on distancing himself from the actions of his team.

Every Monday and Thursday, I send a newsletter to your inbox with the URLs to all the major doping stories in the press over the past seven days. You can read a free example of these round-ups here (link). I publish Long Read investigations on doping in sport, you can find the archive here (link).

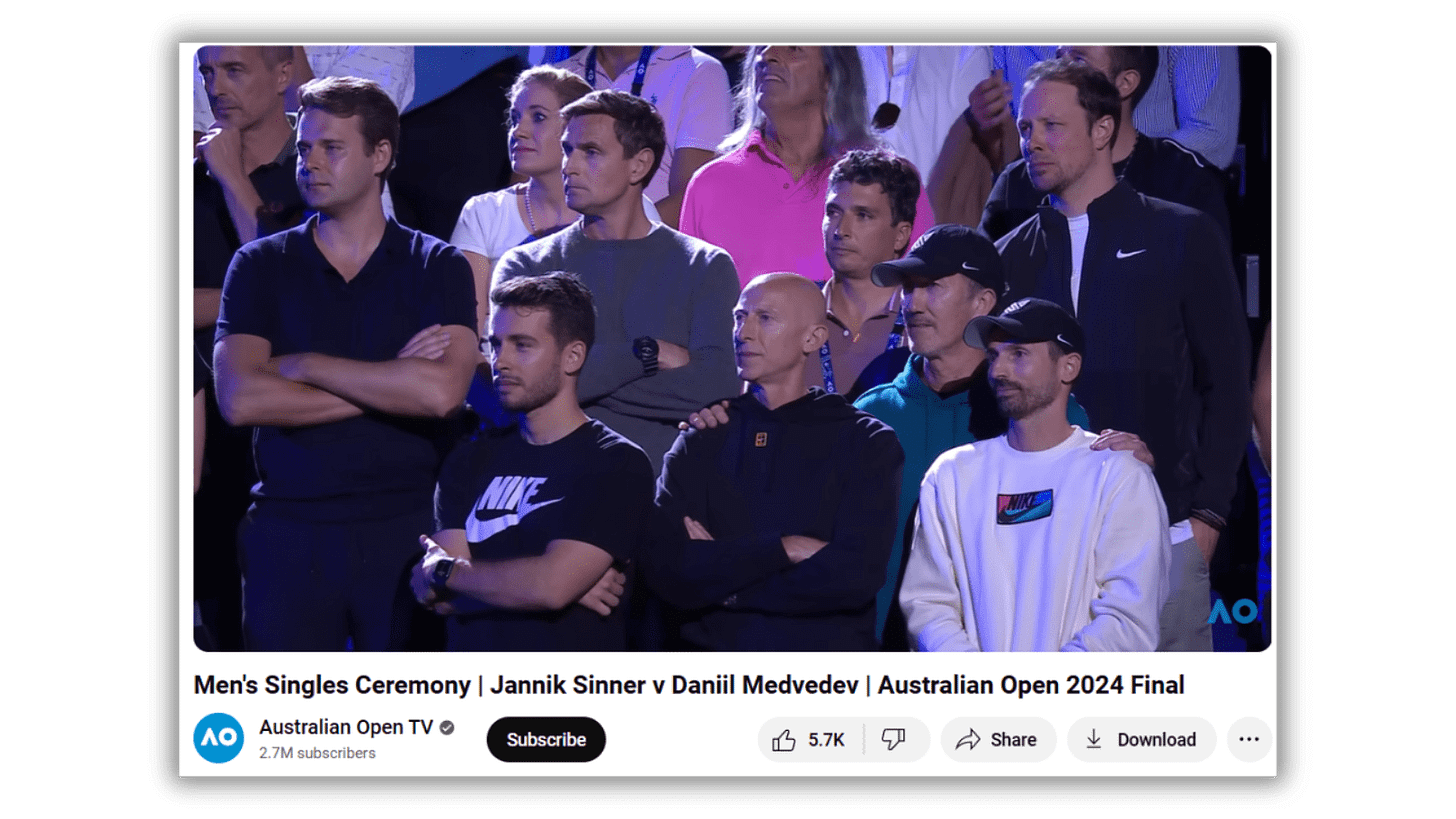

“The teams, they are an integral part of the success of a player, and we have a trophy for those coaches,” said the host of the Australian Open trophy ceremony last weekend. “I'd like to invite Simone Vagnozzi and Darren Cahill to collect their trophy.”

It was at this moment that I was reminded why Jannik Sinner’s career, in the near-term, may be in danger. Three arbitrators will soon decide whether the Italian player will be allowed to defend his Australian Open title next year.

On Sunday morning, Sinner was magnificent in winning his second consecutive title in Melbourne versus Alexander Zverev. In my opinion, the level of play Sinner has now reached on hard court has not been since either Novak Djokovic’s dominant 2011 season or Roger Federer’s five-title streak on the cement courts of New York.

But Sinner, and his legal team, will now enter a peculiar world in which the player will have to distance himself from the very same team that led him to the peak of the sport.

In April, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) will appeal against an independent tribunal’s decision to spare Sinner from a suspension after he failed two tests for the anabolic steroid clostebol in America last year. At the first instance hearing, Sinner was found to have exercised the “utmost caution” to avoid coming into contact with prohibited substances.

The panel members accepted that Sinner had accidently absorbed clostebol during a massage performed by his then-physio Giacomo Naldi, who had been using a clostebol spray to treat a cut on his finger.

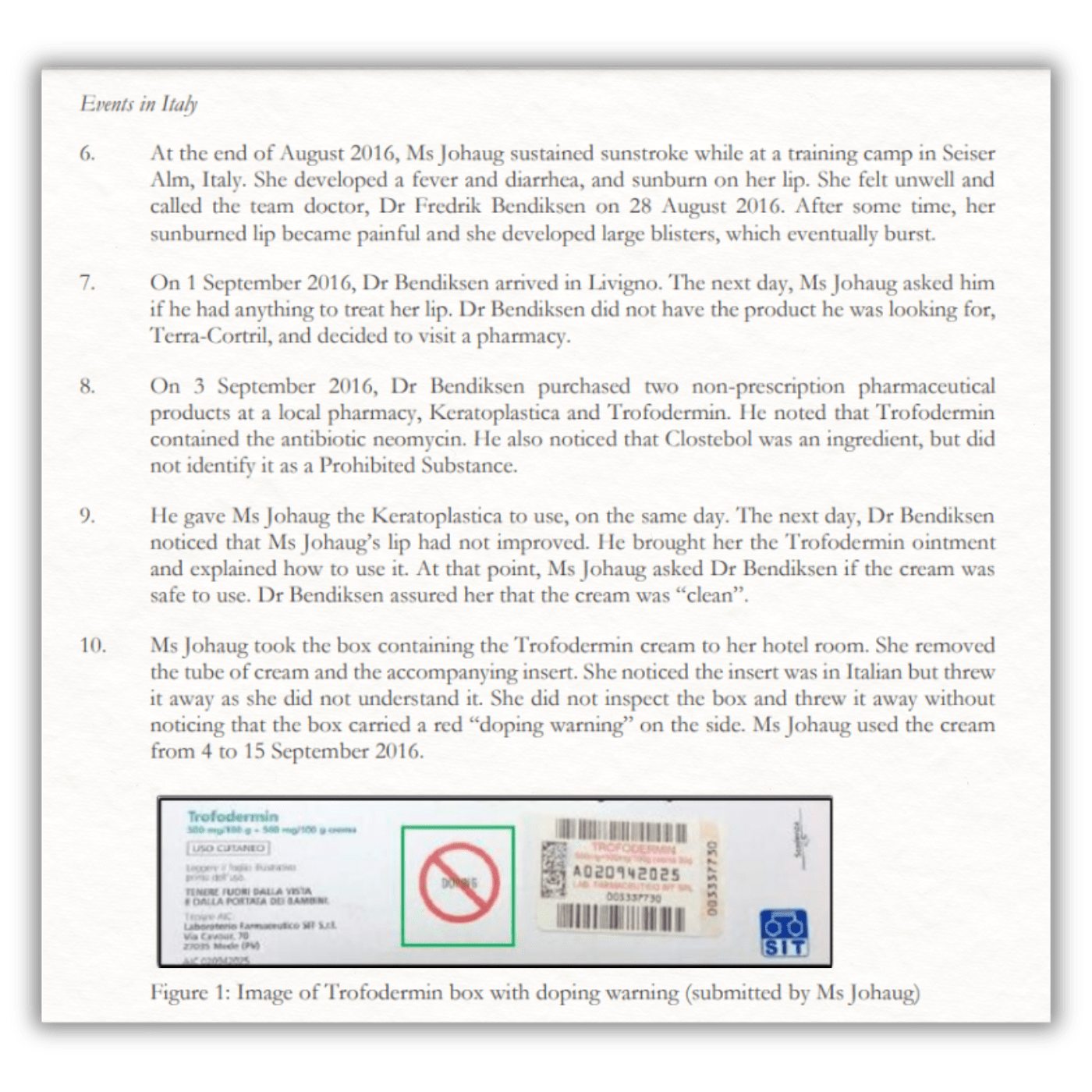

Naldi, who is educated in anti-doping matters, claims to have been unaware that the spray, called Trofodermin, contained a prohibited substance because he did not read the label. However, Sinner’s physical trainer Umberto Ferrara said that he informed Naldi the spray contained an anabolic steroid. Ferrara had purchased the spray in Italy and travelled with it to the USA even though the box was emblazoned with a clear ‘doping’ warning sign.

The crux of the case centred around whether this negligence by Sinner’s team “ought to be directly attributed to the Player”. Article 10.5 of the WADA code is intended to ensure that an athlete cannot simply evade responsibility for a positive drug test by passing that responsibility to members of their team. If athletes could de facto avoid punishment by blaming team members, then the anti-doping system would understandably collapse.

Sinner demonstrated that he had not been at fault because he could not have reasonably known that Naldi had used clostebol on his finger.

“The Tribunal has also concluded that the Player is an individual who exercises considerable caution in respect of anti-doping matters and that he has taken care in choosing his support team and ensuring that they understand and respect the various anti-doping responsibilities,” read the decision.

On Sunday, when I was watching Sinner at the Australian Open trophy ceremony it was Article 10.5 that came to mind.

In acknowledgment of the crucial role of players’ support staff, the Australian Open organisers chose to present his coaches Simone Vagnozzi, from Italy, and Darren Cahill, from Australia, with Australian Open trophies of their own.

When Sinner won the same tournament in 2024, he looked to his team, which then included both Naldi and Ferrara, and thanked them for their instrumental role in his victory.

“My team there, everyone who is in this box, and not only watching from home who works with me we are trying to get better every day even during the tournament we try to get stronger, trying to understand every situation a little bit better so I am so glad to have you there supporting me,” said Sinner.

Ironically at arbitration, Sinner successfully distanced himself from the negligence shown by both Naldi and Ferrara just six weeks later when he failed two drug tests.

If WADA, upon appeal, demonstrates that Sinner is responsible for the actions of Giacomo Naldi then a long suspension is indeed possible.

In 2016, the Norwegian Olympic skier Therese Yohaug, like Sinner, tested positive for clostebol while training in Italy. CAS concluded that Yohaug should have checked whether the clostebol cream she was taking contained banned substances. Her doctor, like Naldi, also failed to do so.

Yohaug was eventually banned for eighteen months. Jannik Sinner can be pleased that one of the panel members who made that decision, Jeffrey Benz, will no longer arbitrate his case.

Whether athletes should ever be suspended in inadvertent doping cases, is an issue for another day. Nevertheless, Sinner committed to adhere by the rules of the Tennis Anti-Doping Programme in the year he twice tested positive for the anabolic steroid clostebol.

Starting in 2023, I investigated why Italian sport is seeing so many clostebol cases (link).

You can read the key summary of event’s in Therese Yohaug case below, as well as the full decision here (link).

Please share this article by using the following link as competing social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, supress Substack URLs:

https://substack-proxy.glitch.me/articles/honestsport-substack-com-p-why-jannik-sinner-could-still-be.html